The importance (and benefits) of having a robust and fair disciplinary process cannot be understated.

Disciplinary procedures are there to:

- deal comprehensively and constructively with employee conduct and (in some cases[1]) performance issues;

- demonstrate reasonableness and fairness on the part of the employer;

- achieve fair outcomes for employees subject to allegations as well as others impacted by the underlying conduct;

- protect the organisation from legal liability and regulatory exposure;

- minimise reputational risks; and

- enhance staff retention and organisational values.

A large part of HR’s role is to apply the employer’s procedures to foster a secure, happy and stable workforce where there are knowable standards of behaviour and accountability. But what does this mean in practical terms when you’re dealing with a live disciplinary issue?

We have put together a list of ‘fundamentals’ below for HR to have in mind throughout any disciplinary process based on queries we frequently receive from our clients. This note is not designed to be an exhaustive checklist, however it is intended to touch on some of the pitfalls and issues that our clients commonly encounter and considers ways of minimising associated risks.

As well as having a proper basis (i.e. a valid reason) to undertake disciplinary action, employers need to follow a fair process to avoid – or defend – legal claims and minimise their employment law risks.

Independence and being clear on who’s who

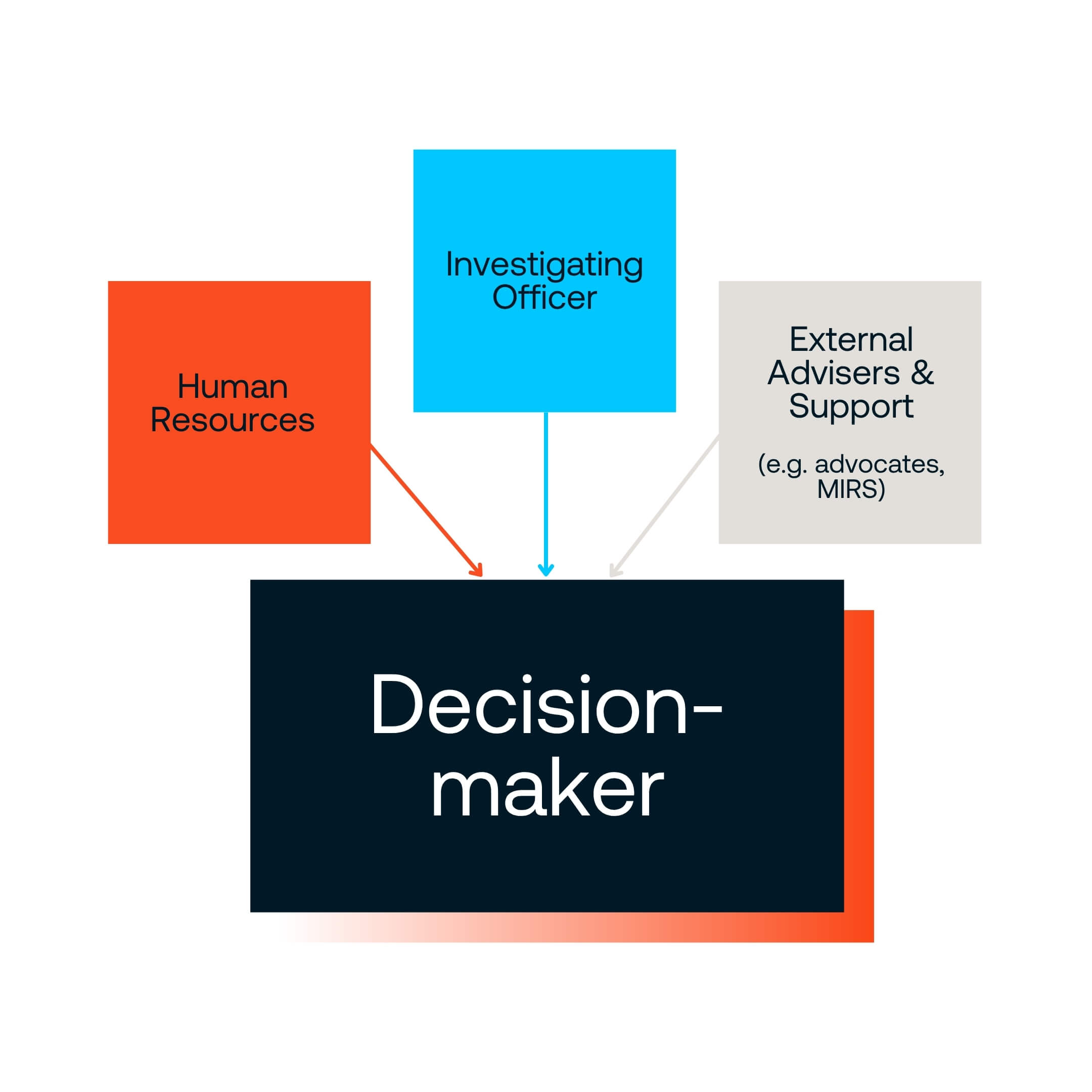

Disciplinary cases are usually referred to HR in the first instance to assess the situation, provide initial advice, and to liaise with relevant parties. HR may involve external advisers if needed and will be on hand to provide any procedural steers and assistance that the decision maker ultimately tasked with resolving the matter requires. One of HR’s most important tasks is to make sure that the various roles required in each process are clearly allocated, the scope of the respective responsibilities is well defined, and timings – as well as expectations around the process generally – are communicated effectively to those concerned.

Although smaller organisations may find it difficult to separate the investigative and decision making functions from a resources point of view, we always recommend that, as far as possible, two separate individuals deal with the investigation and the decision making elements of any disciplinary process, especially where the outcome might result in a final written warning or dismissal. The person who carries out a disciplinary investigation is the “investigating officer” (“IO”) and their role is primarily one of fact finding – i.e. assessing whether there is evidence to support the disciplinary allegations in question. They should also look for evidence which contradicts or undermines the disciplinary case to ensure balance and objectivity so far as possible.

The decision maker (sometimes referred to as the “commissioning officer”) will generally be a member of the senior management team. Their main role in the process commences once any disciplinary investigation is concluded and the IO presents their findings. Whilst the IO should report on facts and may venture an opinion on whether there is a case to answer, the decision maker is usually responsible for deciding whether or not to proceed to a disciplinary hearing. The decision maker should therefore be impartial, free of involvement with the facts of the matter, not have any conflicts of interest, have suitable training and may need expertise in (or at least an awareness of) the underlying subject matter of the allegation(s) if they involve technical points. Disciplinary allegations involving data protection issues or compliance breaches, for example, would particularly benefit from the input of someone with an understanding of, or qualifications in, data protection and compliance respectively. Independence, however, should be the key driver to appointing a decision maker; this is because the independence of the decision maker goes to the heart of whether or not a process is considered fair.

The IO should generally be someone other than the decision maker and should also be able to demonstrate a degree of independence from the employee subject to the disciplinary allegations and the circumstances surrounding them (to avoid accusations of bias). The IO’s role is ordinarily limited to conducting the investigation and making findings of fact based on their investigation. The IO should take care not to creep into the decision maker’s remit by making findings on the disciplinary allegations themselves and/or suggesting disciplinary sanctions. It is becoming more common for organisations to appoint external investigators, especially where the allegations are particularly serious or far-reaching within the organisation or where the investigation of the allegations requires some kind of specialist expertise (such as computer forensics).

Where HR is involved in making arrangements for the disciplinary matter to be investigated, they should give each person involved in the disciplinary process their own ‘terms of reference’ at the outset. This is to avoid mission creep later on in the process. Take care to ensure that ‘off the record’ communications between the decision maker and IO are avoided and that the IO’s role is limited to just that: investigation and fact finding. By clearly defining roles and responsibilities at the outset of a disciplinary process, you can minimise the risk of blurring lines and, ultimately, challenges on the basis of procedural fairness such as ‘collusion’ between the decision maker and IO and/or pre-determination of the issues.

No pre-determination

A common argument raised by individuals undergoing a disciplinary process is that the outcome was pre-determined and the disciplinary process just involved the employer “going through the motions” or was cosmetic only. Because of this, care should be taken to stress that:

- no decisions will be made until all parties have had the chance to put their side across (i.e. until conclusion of the disciplinary process); and

- the disciplinary process is there to determine the outcome and it is only through following the relevant steps (and applying the applicable procedural safeguards) that an outcome will be arrived at.

How do we demonstrate this in practice? All management parties involved should keep an open mind (HR can and should remind the IO and decision maker of this at the outset and subsequently in the process as needed). If anyone appears to have particularly strong views about what did/didn’t happen before the hearing with regard to the nature of the allegations, this is usually a good indicator that they are not impartial or independent enough to hear the case and make a decision on it. Be clear that ‘allegations’ are exactly that until ‘proven’ (i.e. innocent until proven guilty). Ensure the investigation is thorough and fair and makes a genuine attempt to seek the facts from all perspectives. In terms of communications with the employee, ensure they understand the potential outcomes if the allegations are proven (e.g. anything from a written warning to summary dismissal). The requirement to avoid allegations of pre-determination should be balanced with the employee’s right to receive fair warning of the potential outcomes. Language should be appropriately nuanced – e.g. use “in the event that….” or “the potential consequences of this are that…” instead of statements implying strong likelihood or certainty of the outcome.

The contents of any investigation report should also be carefully scrutinised. In this regard, be on the lookout for investigations which:

- do not appear to have taken a balanced approach (e.g. by limiting investigations to the employer’s ‘side’ or disregarding evidence without explanation);

- come to conclusions without reasoning; or

- go further than setting out the investigation’s methodology and results (e.g. by giving opinions on what the outcome of the disciplinary process should be).

For balance, it is also a good idea to ask IOs what matters or facts they could not establish or which remain in doubt. (Although a UK organisation, Acas has templates that can be used to plan and report on investigations, which may be helpful to Isle of Man employers[1].)

Fair warning

The fairness (or otherwise) of an eventual disciplinary outcome is also open to challenge if no, or inadequate, warnings about the potential outcomes of the disciplinary procedure are provided. Make sure, therefore, that you always give the employee fair warning of the possible disciplinary outcomes – usually, these will be set out in the employer’s disciplinary policy or procedural document. These will often be reiterated in the letter informing the employee of the impending investigation (or earlier, on suspension, in cases of serious alleged misconduct). The key is making sure that the potential outcome(s) are communicated without giving any impression (express or otherwise) that the employer has already come to a decision and is only treating the disciplinary process as a ‘rubber stamping’ exercise.

Companions

Employees have the legal right to be accompanied at the formal disciplinary hearing. There is no legal requirement for employers to allow companions to attend investigation meetings although some employers permit this from the point of view of good practice. Employers should bear in mind that, whilst the companion is permitted to accompany the employee at the formal disciplinary hearing, their role can and should be limited to the following:

- summarising the employee’s case

- taking notes

- conferring privately with the employee throughout the hearing (although not to the extent that this compromises the possibility of holding a reasonable hearing)

- summing up the employee’s case at the end of the hearing

The companion is not entitled to answer questions put to the employee or to address the hearing if it is clear the employee is not ‘on board’ with the comments they are making. Additionally, the companion’s presence should not have the overall effect of preventing the employee from explaining their position or of derailing proceedings. Understanding the rights and role of the companion can enable the decision maker (i.e. the person chairing the disciplinary hearing) to maintain control of the meeting or hearing and set some ground rules for how things will be run.

Policies and procedures

At the risk of stating the obvious: having in place a clear and accessible disciplinary policy and/or a procedural document is key to demonstrating fairness. Policies and procedures are essentially the “rules of engagement” for the disciplinary process and the idea is that what is involved should be knowable, with a reasonable opportunity afforded to employees to put their case and, ultimately, be heard.

Policies and procedures need to be detailed enough to allow everybody involved to understand what will happen, what their role is and the potential outcomes by reference to the seriousness of the allegations at hand. They should also provide for the employer’s ability to depart from them if the circumstances of the case require it. The policies and procedures will usually be ‘non-contractual’ to allow the employer some flexibility for this reason.

Any departure from the employer’s published disciplinary policy or procedure should be carefully considered, justified and the rationale documented as to why this is necessary or is considered appropriate in the circumstances.

The disciplinary policies and procedures should be capable of being understood at all levels of the business. Employers will ultimately be judged by how they apply the policies and whether they act consistently with them so merely having them is the ‘starting point’. After all, what use are the procedures if nobody follows them or they are applied so inconsistently that they cannot be regarded as accurate statements of the employer’s practice or policy in relation to disciplinary matters?

Good policies and procedures are more likely on the whole to lead to fair and consistent decision making. That is not to say that having policies and procedures completely removes the risk of fairness being challenged (even the best processes and most experienced managers are likely to be on the other side of a tribunal complaint from time to time), but prioritising an effective disciplinary framework plus training for IO’s and decision makers who conduct such processes, is the best line of defence and invariably a good return on investment.

Cains’ employment team can provide you with a disciplinary policy tailored to your organisation and advise on the practical implementation of disciplinary rules and proceedings including in more complex cases of serious misconduct, where there are related grievances or whistleblowing, and where the situation arises in a regulated context. Get in touch if you would like to discuss the matter with one of our experienced team members.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] https://www.acas.org.uk/investigation-plan-and-report-templates